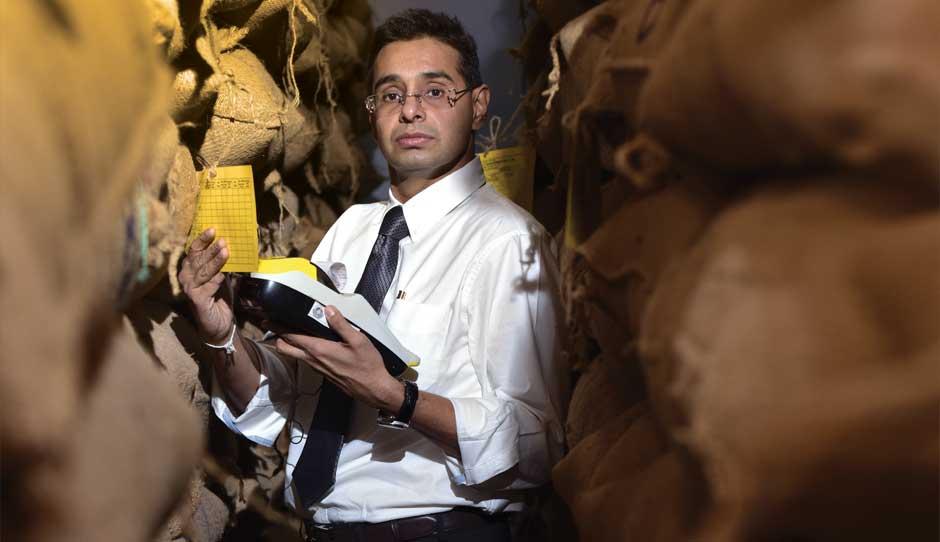

How Sandeep Sabharwal Built a Stockpile of Success

- BY Sonal Khetarpal

In Innovation

In Innovation 15056

15056 0

0

It’s not often one meets an entrepreneur with the decisiveness to shut down a thriving business. Fourteen years after taking over the family firm, Sandeep Sabharwal realised the pulse processing plant that his grandfather had started in the late 1930s didn’t hold good on the type of business Sabharwal wanted to run—a professionally managed corporation that could outlive a family. So, in 2009, he founded Sohan Lal Commodity Management (SLCM), a warehouse management company. In less than five years, the Delhi-based company expanded into procurement, financing solutions and quality assessment to plug the gaps in India’s post harvest agri-logistics. Sabharwal claims SLCM, which now brings in Rs1,100 crore in annual reveneue, has many firsts to its credit, including being the only agri-warehousing company to raise three rounds of venture capital funding.

I have to confess our name Sohan Lal is quite lala. I don’t want to change it though. I want to stick to our roots.” - Sandeep Sabharwal

On Standby

I wanted to have a corporate career just like my father. He was a chief engineer with SIEL Ltd. So, I did the usual graduation and followed it up with a MBA from Fore School of Management in Delhi. But, after graduation there was pressure on me to join the 50-year-old family business of pulse processing started by my grandfather. My engineer father tried running the processing plant for a few years but just could not put on the cloak of an entrepreneur after his retirement. The onus ultimately fell on me. I did resist joining this non-glamorous business by taking up a banking job but gave in to family pressure 3-4 months later.

I joined the business in 1993 and ran it for a good 16 years. Initially, we would process only chickpeas into chana daal but after seven years we had diversified into all kinds of pulses. We had become one of the largest processors of pulses in North India with the processing capacity of 100 metric tonnes a day and 3,000 distribution centres across India.

The Big Dilemma

The pulse processing business was scaling up rapidly. But some questions would perturb me often—what is the net worth of my company? Can I create a niche in this commodity space? Can I turn it into a process driven corporate? The answer to all these questions was a big no. I didn’t want to be in a situation like that of my grandfather where he had to depend on a family member for his company to survive. What if I had refused to help him? I didn’t want all the hard work I had put into the business to go waste. I was intent on building a professionally run organisation that would grow and multiply even after me. For a company to be a corporate, it should have an identifiable revenue stream, an organised marketplace and a well defined USP. I realised the milling business wasn’t that, nor could it ever be.

On crossroads

From 2003, I started thinking about a business that would have all the characteristics I was looking for. Being in the pulse processing business for more than a decade, I knew the pain points all processors face. Like most other processors, we had to sort out the entire logistics ourselves—sourcing crops at the best price, procuring them from farmers in different locations and storing them in warehouses. In taking care of all these factors, the core task of pulse processing would often suffer.

Yes, there are third party warehousing companies we would outsource to but most of them were just places to dump crops. Crop isn’t stored scientifically here. I knew warehousing was a hugely underserved market. So, I thought of filling this gap by providing warehousing services as a third party vendor to farmers, processors and traders.

To test out my idea, in 2005, I started a small pilot project with an 8,000 sq ft warehouse near our processing plant in Delhi. Even though it was a small space the results we got were stupendous. We got nearly 50 queries in just six months. This reiterated my belief in the huge demand for third party warehousing in the post harvest agri-logistics space.

Perception is a business builder’s biggest enemy. Challenge the status quo and ask why its opposite can’t be done.

Script of success

I ran both the businesses for three years but it was difficult to scale up both. Warehousing was already a Rs2.5 crore vertical. Because it had higher growth prospects, I was definitely keener on focusing on it. I am a big believer in a saying by Socrates, “Only an intelligent man knows when to quit.” It was finally in 2009 that I finally got the courage to take the big decision to shut down the pulse milling plant. Obviously, there was a lot of resistance from my family. The pulse processing plant was growing so they couldn’t understand the rationale to shut it down.

Says Sandeep Sabharwal on his work philosophy “I was intent on building a professionally run company that would have the ability to grow and multiply even after me.”

Says Sandeep Sabharwal on his work philosophy “I was intent on building a professionally run company that would have the ability to grow and multiply even after me.” When we started the warehousing vertical, it was easy for us to get customers to store their crops with us. As I said, the demand for third party warehousing was there. We didn’t need to market the our services at all, all we had to do was plug the gap. To make sure we were doing this efficiently, we decided to keep our model infrastructure light. We didn’t buy a single warehouse. Instead, we leased spaces as and when clients—mostly food processors—came up. We would get a processor as a client, lease a warehouse near his plant and then target several farmers from whom he procures crops. We worked backwards on this hub and spoke format. I wanted such a model so I could invest more in technology, working processes and quality of services rather than on buying infrastructure.

For the next two years, we worked on standardising our working processes. We started mapping the laws under the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMCs) which are different in each state of India. We also started documenting different variables such as weather conditions, food crops, clients and government regulations so that we have a well defined process for each of the different conditions we might face. Such detailed documentation helped us create a warehousing model that we could use in any climate, for any crop and in any part of the world. This is still an ongoing process and we are adding as many variables as we come across.

Another thing we leveraged on was technology. From the beginning we installed bar-coded warehousing system so customers could track their food crop right from the warehouse to when it is transported in a truck. All our warehouses are geo fenced so we can track the movement of people and goods and get updates using real time MIS. It also helps us tightly monitor temperature and humidity. We are also the first company to introduce SAP in agri-warehousing space and implement it in a record time of six months. SAP also recognised our project as a first-of-its kind implementation in the world.

Due to the many audits and regular monitoring, our storage losses reduced to 0.5 per cent. The Working Group on Agricultural Marketing, Secondary Agriculture and Policy estimates that lack of storage capacity and inefficient storage techniques result in a massive 10 per cent of total food grain production being wasted annually. This means our processes have led to a reduction of losses by 9.5 per cent. After this achievement, we got our commodity management process patented under the name AGRIREACH and we are the first company in the world to do so. FICCI also did a study on reduction of wastage of food crop using our model and published it as a report Partnership to Scale New Heights: India-US

SLCM is the first company in the world to usher in third party warehousing in a foreign country.

Collaboration in Agriculture.

I think the most radical change we introduced in the warehousing industry was introduction of the “value at risk” model. The practice, even now, is that the cost for storing goods is based on the amount of space used. Even though the space used to store one kilogram of rice is same as that of wheat, the revenue generated by selling the former is more. As a service provider, I felt we should charge a premium for goods based on their value. Since, I am creating more value for the processor by storing rice over wheat, it made sense I charge a premium for goods with a higher value. It is like insurance. Some people are insured at a higher value than others. Initially, we faced a lot of resistance from our customers. They did not want to pay the extra five per cent so we had to undertake the task of educating them on the benefits. This extra amount was like an insurance amount that entitled our company to pay back the market value of goods in case of any storage losses. Initially we had difficulty getting small, price-sensitive customers but bigger companies like Cargill, Louis Dreyfus Commodities, Olam, MMTC, PEC, Glencore, Future Group, Tinna noticed the value we had added and became our clients. By FY2010, we were already a Rs4-crore company with 40 warehouses in 15 locations across India.

The turning point in SLCM’s journey was the call from India-based venture capital firm Nexus Venture Partners in November 2010. Funnily, when Manoj Gupta (a former employee of Nexus) called me, I happily disconnected this call from an unknown number. I figured it would be another pesky credit card company. I finally did pick up the phone the third time they called. We agreed to meet in our office. By May 2010, Nexus decided to invest `10-crore in the company. Even though it was not a huge amount, it instilled a lot of confidence in me as someone from the outside had shown faith in the business model—that warehousing can be done as a service without owning infrastructure. It was more so because no one wanted to venture in this industry. The general mindset was it’s a combination of two dirty words—agriculture and warehousing. We are actually the first company in agri warehousing to have raised funding from a VC.

Our ability to raise venture funding gave us the impression of being different from the regular lala company although I have to confess our name Sohan Lal is quite lala. I don’t want to change it though. I want to stick to our roots. Moreover, Estée Lauder, Gucci, Louis Vuitton are all family names so why can’t Sohan Lal be one. However, I do understand it’s archaic and it will be a challenge to use it in international markets. So, as we grow we will brand the company as SLCM.

We used the funding from Nexus to expand our presence in India to 35 locations and 100 warehouses. Nexus suggested raising a second round of funding. In March 2011, we raised another round of funding of `35.5-crore from Nexus Venture Partners and Mayfield India.

The money helped us add another vertical to our company— procurement. For a buyer, it’s difficult to map which state is offering the crop at best price. Added to that, the production of crops keeps shifting within states. It is time consuming for the processor to keep track of that. Since, we had to follow the crop production trends closely for our warehousing segment, procuring crops at best prices for processors was the next logical move. That way the processor could just come to us to buy the crop and store it with us too. However, we would procure crops only for clients who would store their goods with us. Warehousing is our main product and procurement a value addition and we wanted to maintain that dynamic.

Another value addition we included in our business in 2011 was assaying the quality of goods for different clients. Since we constantly monitor the goods stored in our warehouse we started offering it as a separate service. To existing clients we would offer this service free of charge. As we included these two value additions, our warehouses increased to 200, manpower doubled to 350 in 2011 and our revenue grew to Rs117.97-crore from a mere Rs4-crore the year before.

In 2012, we raised a third round of funding. What amazed me was this time people were hounding us to invest in our company. We got several queries. Finally, Everstone Capital and ICICI along with our former investors Mayfield and Nexus invested Rs125-crore into the company. Together, all the investors own 74 per cent stake in the company.

With this money we bought the Chennai-based non-banking finance company, B.P. Jain Finance & Investments in April 2013 and rechristened it as Kissandhan Agri Financial Services to launch agri-loans. This move completed the jigsaw puzzle of post agri logistics space. What is innovative about this product is, unlike bank loans that look at the client’s balance sheet and assess their ability to pay EMI, Kissan Dhan sees the amount of good the clients have stored in our warehouse and offers 70 per cent of its value as a loan. In the first quarter itself of 2013, we dispersed Rs40-crore of loan and this helped the company reach revenue of Rs521-crore in FY2013.

As we completed the supply chain for post harvest agri-logistics in India, we went global this year, on July 3, 2014, by setting up a subsidiary company to provide warehousing services in Myanmar. We chose Myanmar because from all the third world countries India imports pulses from Myanmar has the largest share. And, just like India, it also does not have any third party warehousing ecosystem. This one move helped doubling our turnover to Rs1,100-crore. We will start offering procurement and financing services too, just as we did in India. We will gradually move to other third world countries as well, most likely, in ASEAN and African regions. This added another feather to our list of firsts—SLCM became the first company in the world to usher in third party warehousing in a foreign country.

Add new comment