How Total Environment is Building on Bricks, Grit and Beauty

- BY Shreyasi Singh

In Strategy

In Strategy 22568

22568 0

0

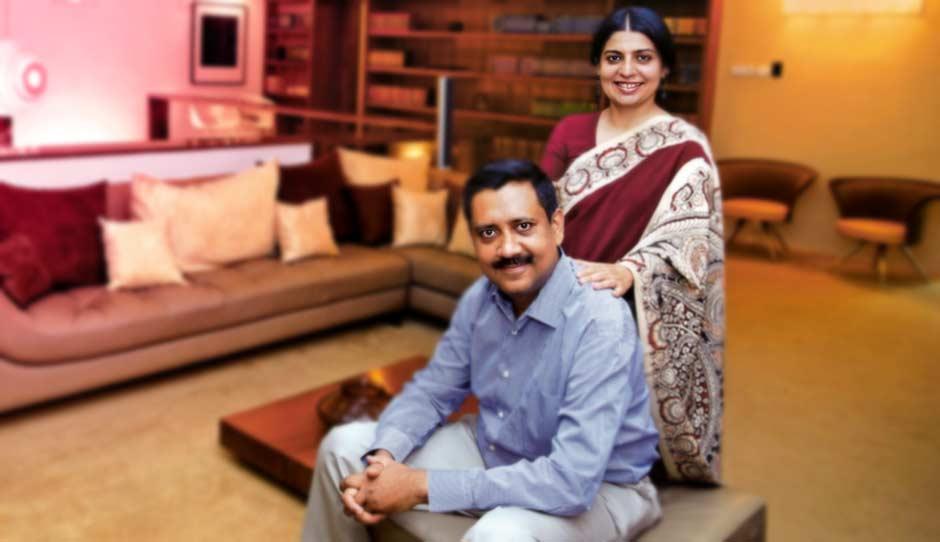

Kamal and Shibanee Sagar have truly taken the road less travelled. Founders and principal architects of Total Environment, a Bengaluru-based real estate development firm, this husband-wife duo certainly aren’t your regular builders—both by design, and by nature. In an industry that thrives on mass-scale housing and broken promises, the Sagars’ business foundation is laid on attention to detail, unprecedented customisation and an unyielding aspiration to make homes, not houses. That this took them to a turnover of Rs170 crore last fiscal, from sales of 109 apartment units, is incidental, they insist. Even after 15 years, sensitively designed, well-built and lived-in homes continue to be their only vision.

In 1997, while working on their second project, Green is the Colour, a residential complex of 44 apartments on Bengaluru’s Bannerghatta neighbourhood, Shibanee and Kamal Sagar, the project’s architects, decided they wanted each flat to have a garden. “An apartment without its own garden just didn’t feel like a home,” says Kamal. So, the duo added floor area to their units, and gave every apartment a cantilevered terrace garden, essentially a little sit-out with a patch of green. Each garden was designed to be of double height, facing different directions on different floors so that each got enough sunlight for the plants to grow. The only hitch: customers had paid up according to the square footage of the original design, and refused to fork out more money. Still, the Sagars didn’t budge. “We actually did it for free,” they say.

The decision squeezed further the tiny profits—Rs 8 lakh—they ended up making on that project. It wasn’t an easy call, especially because Green is the Colour was to help recover the Rs 20 lakh-plus they had netted in losses with their first project, Cirrus Minor, a year before. But design trumped commerce. They brought the outdoors in, and planted deep roots for their firm’s ethos, aptly named Total Environment.

A terrace garden might be almost mandatory for upmarket residential projects today, say the Sagars. But, in 1997, no residential complex boasted of a terrace garden in every apartment, anywhere in the world, they claim. “We introduced the concept. It sounds dramatic, but it isn’t. It’s a simple idea that is quite easy to implement.”

The Sagars’ business foundation is laid on attention to detail, unprecedented customisation and an unyielding aspiration to make homes, not houses.

Since then, every Total Environment home—600-plus over the past 15 years— has come with a garden. “We just don’t build without one.”

Much like the way that tiny patch of green has flourished into larger, more innovative gardens in their subsequent projects, Total Environment has also blossomed beautifully. Last year, the 365-people company, which has till now completed more than 28 residential and corporate projects, notched sales of more than Rs 170 crore. Though its footprint is mostly limited to Bengaluru, with recent forays into Pune and Hyderabad, the Sagars are now being noticed as builders of high-quality, award-winning homes.

The Foundation

The au contraire streak of the Sagars has been a constant companion for Total Environment. Co-founded in 1995 with three of their friends (all of them were in their mid-20s), the company was laid on a simple foundation: to make homes worth living in. Young and idealistic, they managed to sell out their first project, a residential complex of 12 apartments called Cirrus Minor, within a month, mainly because of Kamal’s impressive work at the Poonawalla stud farms in Pune, right after his architecture degree from IIT Kharagpur in 1992.

Each flat in Cirrus Minor was sold for around Rs 10 lakh. But the young entrepreneurs had got the math wrong. Building to their specifications—mirror polished kota stone floors, imported craftmaster doors, form-finished concrete beams, wire-cut brick masonry from Kerala—the project cost climbed up to Rs 1.32 crore without including team salaries, office rentals and other costs. Kamal, the group’s nucleus, was advised to tone down the specs and bring it within the Rs 1.2 crore capital that they had. “But that seemed like a pointless way to go about it. We plunged right into it and built it the way we wanted to,” he recalls.

The losses hurt, but they also gave the company a fait accompli—build more to break even. “There is no idealism here. We have to sell, of course. But design has always been the priority. Commerce comes in second,” says Shibanee calmly.

Short of cash, they needed to sell the flats in advance to fund land acquisition and begin construction. At the time, Bengaluru was becoming a global technology hub. Kamal saw an opportunity here and made presentations to IT firms like Wipro, Infosys and others, offering to build housing for their employees. Employees of Microland and Sasken signed on Total Environment, and imaginatively-named projects like Green is the Colour and Bougainvillea followed.

Their aesthetic but functional, eco-conscious yet technically superior homes, undoubtedly pleased customers. And their idealism also found many takers. One of their early land sellers (for the Green is the Colour site) in the late 1990s, was amazed that they had sold the land they bought from him to Microland at exactly the same price—Rs 500 per sq ft—without any margin at all. He offered the couple (by then their other co-founders had amicably drifted to pursue other career options) two adjacent plots of land without an upfront payment. “Pay me from the proceeds of the sales in the project,” he told the young couple.

“This was a turning point. We sold our apartments in the open market at Rs1,200 sq ft,” Kamal recalls. It finally led them to profits at the turn of the century.

The Innovations

More than proving business sustainability, the Sagars’ skill has been in learning quickly. Within their first few projects, they saw the gaps other developers weren’t plugging. For one, they realised that the practice of “force fitting” families with different needs—ageing parents, pets, children—into a standard home layout led to dissatisfaction and ad-hoc renovations. “At the site, we’d see people ask construction staff to move this wall, and add that shelf. There would be requests to change marble to tiles. It was crazy because there was so much breakage and redoing. Timelines would also go haywire,” Kamal says.

So, the couple decided that after they had sold the apartment to a family, they would sit down with them to understand their specific needs and aesthetic sensibilities. These would be worked into the flat design and a new customised plan put forward. Their early customers, many of whom are repeat buyers, admit it has been this approach, more than anything else, that has made them Total Environment “converts”.

“I remember spending around three hours in a marble store on Hosur Road with Kamal and Shibanee. Even in choosing the colour of the laminate for the kitchen, they’d be involved,” says Jessie Paul (also an Inc. India columnist), who bought her first-ever home in Green is the Colour. Since then, she’s invested in other Total Environment projects like Free Bird, The Good Earth (where she lives now) and Windmills of Your Minds. In an era, when mass-scale housing is the real profit-spinner for construction companies, nobody allows you this level of customisation, Paul says.

Anand Sukumar, another Total Environment faithful, and CEO of GK Vale, an iconic chain of photography stores in Bengaluru, agrees completely. In 2004, when his family bought two 1,950 sq ft flats in Shine On 2, he gave the Sagars a wishlist—convert the six bedrooms into a four bedroom apartment. There were several columns on which the building’s foundations were supported and breaking them was problematic, he remembers. Some of them could be broken down, others couldn’t. Sukumar still marvels at how beautifully they adapted the flat.

“Today everything in the apartment seems like it was done by design, as though this is how it was planned to be. Also, our interaction with them was phenomenal,” he says. Though Sukumar continues to invest in residential and commercial properties by established builders (Mantri and Brigade) across Bengaluru, he says if he’s buying his home, he wouldn’t look at anything but Total Environment. “No one else can give you the feeling that you’re actually building your own home, like they can. It isn’t about buying into a project.” Shibanee, who Paul calls the interior design whiz of the two, says she has fond memories of these houses. In fact, she remembers being so involved in some of the apartments—right down to where the 10 kilo rice and wheat tins would be kept in the kitchen—that the joke in their office was, “If you can’t find the dal, you better ask Shibanee.”

Clearly, their gut proved right. Customisation became such a selling point for them that over much of the last decade, Total Environment has spent more than Rs 10 crore in converting this insight into a software tool called eBuild. The software helps customers see for themselves what’s possible and what’s not, and how the changes—walls knocked down or moved around, flooring or kitchen counter material altered—that they want will eventually look. Every time the design is altered, eBuild also shows the subsequent cost impact. The software has helped them streamline the customisation process, and is less human resource intensive.

Neeraj Bansal, associate director in KPMG’s real estate practice, says customisation can definitely be a niche differentiator for a builder in the crowded residential market. He cautions though, that when trying to scale up, as Total Environment wants to, customisation requires a sound back-end and mature processes. “You have to get the inventory and procurement right,” explains Bansal. Total Environment is confident they’ve got that covered, thanks to the two key decisions they took early on: bringing all construction in-house and creating their own capability lines; and by taking on the unglamorous, messy job of managing their properties.

That’s smart thinking, KPMG’s Bansal admits. “Many prominent builders are now re-looking at their facility management because they’ve realised that seeing this as a long-term objective, not an end-of-the-cycle function has many advantages. Better-maintained properties appreciate more, and it helps to continue relationships with customers.”

As has been their style, the Sagars were early movers of this logic. Every project since Cirrus Minor, their first, continues to be maintained by them. It’s helped them to improve on their design, and to understand what was working and what wasn’t, they say. “Everything we’ve done is planned,” says Abraar Ahmed, a civil engineer who has been with the company since 1998.

Take their woodworking unit, he says. Because they could not control the quality they sought by contracting out their carpentry requirements, Total Environment set up its own woodworking factory.

“Our shop floor is only 25 per cent occupied. We’ve planned ahead for the next 20 years,” claims Ahmed.

The Master Plan

Windmills of Your Minds in Bengaluru’s Whitefield is one of the Total Environment's most ambitious project.

Windmills of Your Minds in Bengaluru’s Whitefield is one of the Total Environment's most ambitious project. Windmills of Your Minds, their 24-acre, 400-unit project in Bengaluru’s Whitefield is their most ambitious yet. Started in 2007, it was the prototype of the duplex apartment at Windmills—and it’s strategically placed advertisement in publications like The Economist—that first catapulted Total Environment to recognition beyond its hometown. “Every developer from around the country came to know of us,” says Kamal, admitting the attention took him by surprise. They’d build the prototype (where the pictures in this story have been shot) because they were finding it difficult to sell the large, 5,924 sq ft apartment, which today costs upwards of Rs 4 crore.

The high-profile project has given them several sleepless nights too. During the recession in 2008, many customers backed out, and others defaulted on payments. Through its journey, stretched timelines have been Total Environment’s Achilles Heel. It’s an accusation the Sagars bristle at but can’t ignore. After the hype it had gathered, and the kind of clientèle it had attracted, they knew they had to ensure that—sales or no sales—work continued on Windmills. So they approached several banks to invest into the project. In March 2009, after Kamal made a presentation to HDFC chairman Deepak Parekh, the bank put in Rs 130 crore through a structured deal (part equity, part return). Today, phase one of Windmills is complete. Nearly 100 units, each one of them completely customised, have been handed over.

Along with finishing Windmills, they’re also excited about spreading their footprint to Hyderabad and Pune. “We’re looking at Rs 250 to Rs 300 crore in turnover in the next couple of years,” they say, after much prodding. “But that’s not a milestone. Numbers have no meaning. They don’t excite us at all,” claim the Sagars. Fortunately, some things never change. Hitting braver aesthetic milestones remains their only aim.

Add new comment